Predictable Financial Crises

- Greenwood, Hanson, Shleifer, Sorensen

- Journal of Finance, forthcoming

- A version of this paper can be found here

- Want to read our summaries of academic finance papers? Check out our Academic Research Insight category

What are the Research Questions?

Who among us wouldn’t want to be the savior that predicts a market crisis and saves our clients from losses in capital — or even better — profits from them? A central topic of interest for academics is whether there are more precise tools to predict financial crises. Those who believe so dedicate their efforts to finding early warning indicators.

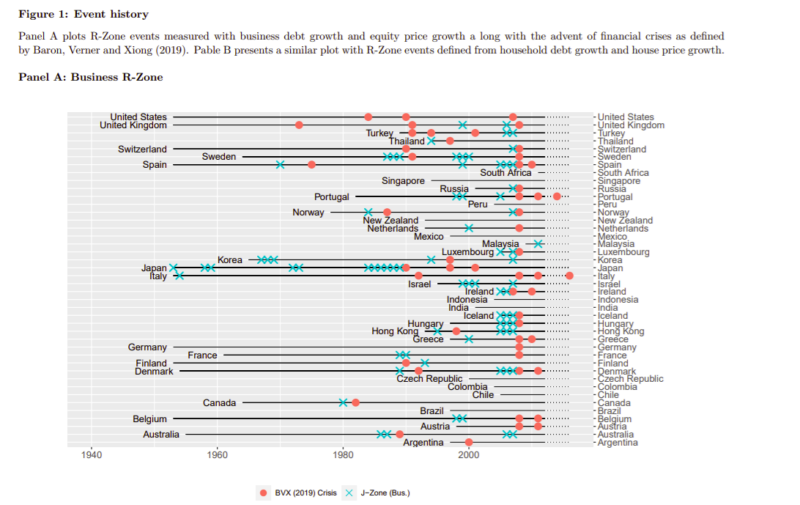

In this paper, the authors estimate the probability of financial crises as a function of past credit and asset prices growth. They borrow from the work by Baron et al. (2021), which improved existing crisis chronologies and combine historical data on the growth of outstanding credit to nonfinancial businesses and households with data on the growth of equity and home prices to estimate the future probability of a financial crisis in a panel of 42 countries over the period from 1950 to 2016.

What are the Academic Insights?

By designing two “red zone” indicators ( a business-related indicator and a household related indicator), the authors find:

1. Crises can be predicted using past credit growth in simple linear forecasting regressions. Specifically, both nonfinancial business and household credit growth forecast the onset of a future crisis, BUT the degree of predictability is modest, even at horizons of up to five years.

2. The degree of predictability rises substantially when the focus is on large credit expansions that are accompanied by asset price booms. When nonfinancial business credit growth is high and stock market valuations have risen sharply, or when household credit growth is high and home prices have risen sharply, the probability of a subsequent crisis is substantially higher (14% at the one-year horizon and 45% within the next three years). All this means that, even after entering the R-zone, crises are often slow to develop, suggesting that policymakers have time to act based on early warning signs. For example, their finding was that the United States was in the household R-zone from 2002 to 2006 ahead of the financial crisis that arrived in 2007.

3. Overheating in the business and household credit markets are separate phenomena that independently predict the arrival of future crises. Specifically, 64% of the crises in our sample were preceded by either a household or a business R-zone event within the prior three years. These two forms of overheating are particularly dangerous, however, there are rare instances in which they occur in tandem (e.g., Japan in 1988).

4. Overheating in credit markets has a global component and is correlated across countries.

5. R-zone events predict future contractions in the real gross domestic product (GDP), defined as a 2% decline in real GDP in a given year.

The authors performed a number of robustness tests.

Why does it matter?

This study contributes to the literature in a number of ways: it documents the strength of the interaction effect between credit growth and asset price growth using a simple and transparent methodology and it uncovers a higher degree of crisis predictability than has been documented in prior studies.

The Most Important Chart from the Paper:

Abstract

Using historical data on post-war financial crises around the world, we show that the combination of rapid credit and asset price growth over the prior three years, whether in the nonfinancial business or the household sector, is associated with a 40% probability of entering a financial crisis within the next three years. This compares with a roughly 7% probability in normal times, when neither credit nor asset price growth is elevated. Our evidence challenges the view that financial crises are unpredictable “bolts from the sk” and supports the Kindleberger-Minsky view that crises are the byproduct of predictable, boom-bust credit cycles. This predictability favors policies that lean against incipient credit market booms.